S3 server access logs at scale

-

Nurdan Almazbekov, Infrastructure Security

- Sep 26, 2025

Introduction

Yelp heavily relies on Amazon S3 (Simple Storage Service) to store a wide variety of data, from images, logs, database backups, and more. Since data is stored on the cloud, we need to carefully manage how this data is accessed, secured, and eventually deleted—both to control costs and uphold high standards of security and compliance. One of the core challenges in managing S3 buckets is gaining visibility into who is accessing your data (known as S3 objects), how frequently, and for what purpose. Without robust logging, it’s difficult to troubleshoot access issues, respond to security incidents, and ensure we are retaining only data that is actually necessary. This is a challenge faced by many companies using S3.

Historically, enabling S3 server access logging (SAL) wasn’t straightforward. Storage of raw logs was expensive, logs were slow to read and certain Amazon Web Services (AWS) features such as date-based partitioning for S3 server access logs, which is essential for Athena querying, was only added in November 2023. Therefore, object-level logging, that is tracking access to every S3 object, was historically difficult to justify due to cost and complexity. However, as our operational needs and industry expectations evolved, the necessity for better logging became clear. Object-level logging now helps us troubleshoot permission issues, identify unused data for clean up, and provide confidence to third-parties that we are managing sensitive data responsibly.

In this post, we cover how we overcame storage and data management challenges, what worked (and didn’t work), and what we’ve learned operationalizing S3 logging at scale. We are excited to see how these capabilities will enable new workflows and improve our data security posture as we continue to gather more historical data.

What are S3 server access logs?

S3 server access logs contain API operations performed on a bucket, as well as its objects. Logging is enabled per S3 bucket by providing a storage destination; another S3 bucket is recommended due to circular logging. Once the resource policy allows putting objects, logs will start arriving at the configured destination. A SAL log line may look as follows,

4aaf3ac1c03c23b4 yelp-bucket [20/Nov/2024:00:00:00 +0000] 10.10.10.10 - 09D73HFNSX17KY60 WEBSITE.GET.OBJECT foo.xml.gz "GET /foo.xml.gz HTTP/1.0" 200 - 587613 587613 83 79 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko; compatible; bingbot/2.0; +http://www.bing.com/bingbot.htm) Chrome/116.0.1938.76 Safari/537.36" - <host-id> - - - yelp-bucket.s3-website-us-west-2.amazonaws.com - - -

Here’s more legible view as a table for some of the fields,

| file_bucket_name | remoteip | requester | requestid | operation | key |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yelp-bucket | 10.10.10.10 | - | 09D73HFNSX17KY60 | WEBSITE.GET.OBJECT | foo.xml.gz |

Delivery of access logs is best-effort, meaning a log may occasionally be missed, arrive late, or have duplicates. From our evidence, less than 0.001% of SAL logs arrive more than a couples days later. For example, we witnessed some logs arriving 9 days later.

Why we want them (how to use them)

Object-level logging improves debugging and incident response processes and allows identifying unused files so that they can be deleted. Here’s how you might use them.

Debugging

We sometimes have systems with many abstraction layers, and folks using them often have a hard time debugging access issues. Those server-side logs are very much appreciated to hasten the debugging process. The usual scenarios slice it for a specific timestamp and object prefix, as those are two known facts when debugging those types of issues. With the results, you can confirm if your system actually uses the correct identity, whether it accessed the expected objects, and if it was denied or not:

SELECT *

FROM "catalog"."database"."table"

WHERE bucket_name = 'yelp-bucket'

AND timestamp = '2025/02/05'

AND key = 'object-i-cant-read.txt'

Cost Attribution

Let’s say you have a S3 bucket with substantial costs, and you can’t figure which service is generating all the calls, you can use something like this to figure out the main culprits:

SELECT

regexp_extract(requester, '.*assumed-role/([^/]+)', 1) as iam_role, operation, COUNT(*) as api_call_count

FROM "catalog"."database"."table"

WHERE bucket_name = 'yelp-bucket'

AND timestamp = '2025/02/05'

AND requester LIKE 'arn:aws:sts::%:assumed-role/%'

GROUP BY 1, operation

ORDER BY api_call_count DESC;

This will group all API calls per IAM role requester. You’re now one step away from calculating the cost per requester! Something similar can be done if you instead use IAM User.

Incident response

If you’ve found indicators of compromise around S3 access, you can slice SALs using whatever fingerprint you have about the compromise. Whether it is the IP address, the user-agent field, or the requester field, you’ll be able to see what data was accessed and assess the size of the attack. Below is an example of an initial exploration of what buckets were accessed by the compromised role, since the first known indicator of compromise.

SELECT DISTINCT bucket_name, remoteip

FROM "catalog"."database"."table"

WHERE requester LIKE '%assumed-role/compromised-role%'

AND timestamp > '2024/11/05'

Data Retention

With joining S3 inventory with S3 server access logs, you can figure out what data stays unused in your buckets, and delete it based on its last access time. This is good for multi-tenants buckets or with buckets related to complicated systems where an expiration lifecycle policy would be too broad to be used safely. We are comfortable relying on best-effort delivery of S3 server access logs when deleting unused objects, since our retention periods are much longer than the maximum log delay. In addition, deletions are based on prefixes—so missing all logs for a given prefix would only occur for truly inactive data.

Parquet format to the rescue

Parquet is a columnar data format that stores columns in a row group where each column (consisting of pages) is laid out sequentially, making it ideal for compression. It includes metadata that allows skipping row groups or pages based on filter criteria which reduces data scanned.

Since S3 server access logs write to the destination bucket continuously, it results in producing many small S3 objects. Those small objects present a significant challenge. Not only do they prevent us from compressing them easily, it also significantly impacts Athena query time made against the raw logs, and make the transition cost to other storage classes pricier than necessary. Therefore, merging into fewer objects provides a significant reduction by simply putting all logs together in fewer objects.

Alternatives

As an alternative, AWS provides a ready solution to log object-level events as CloudTrail Data Events, but you are charged per data event so it’s substantially more expensive: $1 per million data events - that could be orders of magnitude higher!

Volume of logs

We generate TiBs of S3 server access logs per day. By converting raw objects to parquet-formatted objects in a batch, the process we call “compaction”, we are able to reduce storage size by 85% and the number of objects by 99.99%. Compacted logs are useful for querying over small time windows, but for other use cases the logs are further reduced using aggregates. For example, we created additional access-based tables for queryability over a long period of time.

Architecture

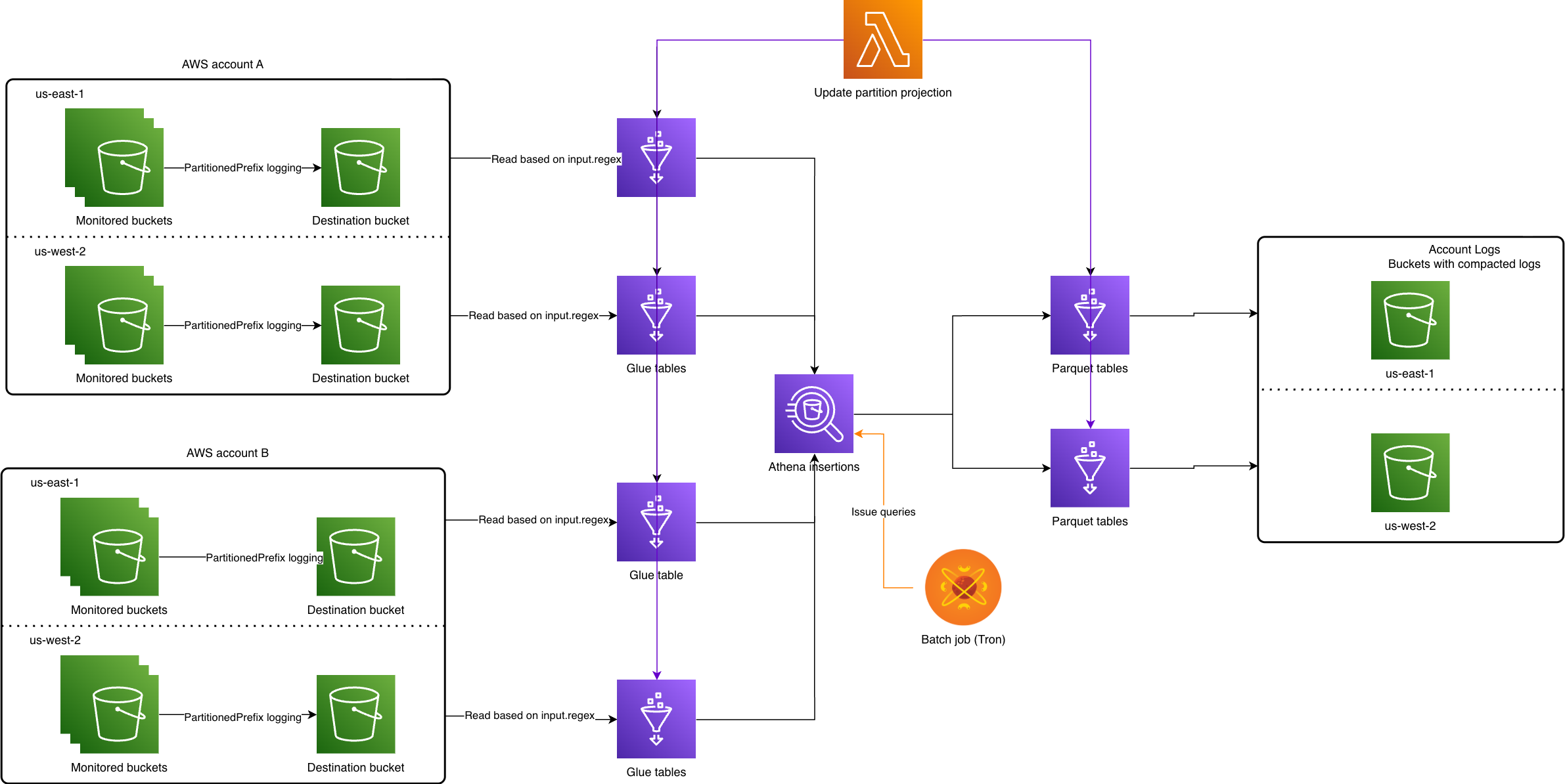

We were inspired by an AWS blog post, which gives a high-level description of a possible architecture to determine unused objects on a bucket. The idea is to perform disjunction between S3 inventory with S3 server access logs to determine unused objects for a period of time. The work focused on the compaction part of the process because it involves setting up Glue tables, running insertion queries, and expiring objects via tags that have been inserted which essentially touch on all the main problems.

Each monitored bucket has a destination bucket that must exist in the same account, as well as region to eliminate cross-region data charges. Tron, Yelp’s in-house batch processing system, runs daily and converts the previous day’s logs to parquet format via Athena insertion queries. A Lambda is used to enumerate all possible bucket names because we opted to use a projection partition using enum type (explained more in Partitioning). So after compaction, logs in parquet format are consolidated in a single account. Most of the effort was spent on making the process robust so that no manual intervention is needed for them.

Mechanism for deleting compacted logs

Following a successful insertion, the underlying S3 objects for SAL logs are tagged for expiration via lifecycle policy. The bucket needs to have an S3 lifecycle policy to delete objects based on tags, and allow an entity to tag objects. That’s the only scalable way to delete per object without needing to modify lifecycle policy each time or issuing delete API calls.

As for logs that arrive after an insertion, we decided that the straggler logs can be ignored to deliver business value in a timely fashion. The straggler logs can be inserted at a later time after tagged objects have expired.

Infrastructure setup

Terraform management

A single AWS account is used for querying between different accounts. The benefit is that you can use a single role to access resources from other accounts, without having to pivot between roles or switching accounts in the AWS console. This is where resource management tools like Terraform come in handy, though there’s still operational load to configure access. Glue tables are created per account per region to make SAL logs queryable in Athena with special attention to log format in input.regex. Then, SAL logs get converted to parquet-formatted objects (as described in Compaction of SAL logs).

Format for TargetObjectKeyFormat

The first step is to enable access logging by creating destination buckets for access logs. But first, we had to take care of buckets that already had SAL enabled. The buckets used the default format of SimplePrefix which produces a flat prefix structure.

[TargetPrefix][YYYY]-[MM]-[DD]-[hh]-[mm]-[ss]-[UniqueString]

Inevitably, the accumulated volume of logs for these buckets with SimplePrefix became impossible to query in Athena due to S3 API rate limits. As there’s no way to slow down reads from Athena, data partitioning is one of the ways to solve the issue.

PartitionedPrefix comes with more information to use to partition data, specifically account ID, region and bucket names.

[TargetPrefix][SourceAccountId]/[SourceRegion]/[SourceBucket]/[YYYY]/[MM]/[DD]/[YYYY]-[MM]-[DD]-[hh]-[mm]-[ss]-[UniqueString]

Once we made PartitionedPrefix format default in the Terraform module, we migrated existing target prefixes so newer logs use the correct format. For the delivery option, we chose EventTime delivery because it gives the benefit of attributing the log to the event time.

Reading S3 server access logs

In the following sections, we cover schema properties for reading SAL logs.

Partitioning

We chose Glue’s projection partitioning over managed partitions because it requires refreshing partitions (using commands like MSCK REPAIR or ALTER TABLE), which can become cumbersome as the number of partitions grows. This can lead to increased query planning times due to metastore lookups, and will need to be addressed with partitioning indexing.

With partition projection, we avoid this overhead by using the known log prefix format.

'storage.location.template'='s3://<destination-bucket>/0123456789012/us-east-1/${bucket_name}/${timestamp}'

Where the bucket_name partition key uses enum so all possible bucket names are written to it. While the timestamp partition key encompasses an entire day, that is yyyy/MM/dd, which accelerates query pruning time because we typically query a day’s worth of logs. Using a more fine-grained partition would lead to over-partitioning.

The main risk is accidentally missing logs from new buckets in our querying system. Since we chose the enum partition type for ease of querying across all buckets, the partition values for bucket and account in Glue tables are kept up-to-date by a Lambda job. The Lambda reads from an SQS queue that gets data populated by periodic EventBridge rules —the queue is necessary to avoid concurrent reads and writes.

The alternative of injected type alleviates the need to enumerate all possible values but requires specifying a value in where-clause. We decided to use an injected type for access-based tables because of their specific use case. Another consideration is that if enum type partition is not constrained in the where-clause, the query may run into a cap of 1 million partitions over long time windows.

Log format in input.regex

Once you have logs with partitioned prefix, a regex is provided that allows the Glue table to read the logs.

WITH SERDEPROPERTIES (

'input.regex'='([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) \\[(.*?)\\] ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) (\"[^\"]*\"|-) (-|[0-9]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) (\"[^\"]*\"|-) ([^ ]*)(?: ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*) ([^ ]*))?.*$')

While the pattern can be difficult to read, it quickly becomes clear that patterns such as \"[^\"]*\" won’t hold if there’s a double quote inside double quotes, or spaces for ([^ ]*). We realized that some of the fields are user-controlled, meaning a user can supply any characters to fields such as request_uri, referrer, and user_agent, which are written without any encoding.

Here’s a simple way to break up the above regex using the referrer HTTP header,

$ curl https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/foo-bucket/foo.txt -H "Referer: \"a b\" \"c" -H "User-Agent: \"d e\" \"f"

The resulting log has double quotes (“) appear within the field without encoding or escaping whatsoever.

e383838383838 foo-bucket [28/Nov/2024:04:19:03 +0000] 1.1.1.1 - 404040404040 REST.GET.OBJECT foo.txt "GET /foo-bucket/foo.txt HTTP/1.1" 403 AccessDenied 243 - 10 - ""a b" "c" ""d e" "f" - <host-id> - TLS_AES_128_GCM_SHA256 - s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com TLSv1.3 - -

No surprise, we have encountered other logs with malicious text in request_uri and user_agent fields that break regex matching as well.

e383838383838 foo-bucket [20/Nov/2024:22:57:55 +0000] 1.1.1.1 - 404040404040 WEBSITE.GET.OBJECT public/wp-admin/admin-ajax.php "GET /public/wp-admin/admin-ajax.php?action=ajax_get&route_name=get_doctor_details&clinic_id=%7B"id":"1"%7D&props_doctor_id=1,2)+AND+(SELECT+42+FROM+(SELECT(SLEEP(6)))b HTTP/1.1" 404 NoSuchKey 558 - 26 - "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64; rv:109.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/117.0" - <host-id> - - - foo-bucket.s3-website-us-west-2.amazonaws.com - - -

e383838383838 foo-bucket [01/Jan/2024:01:01:01 +0000] 1.1.1.1 - 404040404040 REST.GET.OBJECT debug.cgi "GET /debug.cgi HTTP/1.1" 403 AccessDenied 243 - 13 - "() { ignored; }; echo Content-Type: text/html; echo ; /bin/cat /etc/passwd" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/100.0.4867.123 Safari/537.36" - <host-id> - - - foo-bucket.s3.amazonaws.com - - -

Essentially, any regex pattern for parsing S3 server access logs can be broken by a counter example that includes delimiters.

Fortunately, the first seven fields are not user controlled; with the key being url-encoded twice, for most operations - see Idiosyncracy in key encoding. Since the rest of the fields were less critical to us than the requestid and key, non-encoded fields are wrapped in an optional non-capturing group, i.e. (?:<rest-of-fields>)?. Thus, we ensure that the first seven fields are present even if the rest of the fields fail regex matching. An important takeaway is that if a row is empty, then the regex has failed to parse that row— so don’t ignore those!

For anyone wondering why the regex ends with .*$: it accounts for the possibility of additional columns being added at any time.

Compaction of SAL logs

Limitations of Athena

We took advantage of issuing parallel Athena queries but Athena is a shared resource so a query may be killed any time due to the cluster being overloaded, or occasionally hitting S3 API limits. Given our scale, we would encounter such errors on a regular basis. Therefore, we needed a way to retry queries that were limited by the quota on the number of active Athena queries at a time.

During the initial runs, we encountered TooManyRequestsException Athena exceptions that we addressed by both reducing concurrent queries and requesting an increase in active Data Manipulation Language (DML) queries for each affected account and region.

Queue processing

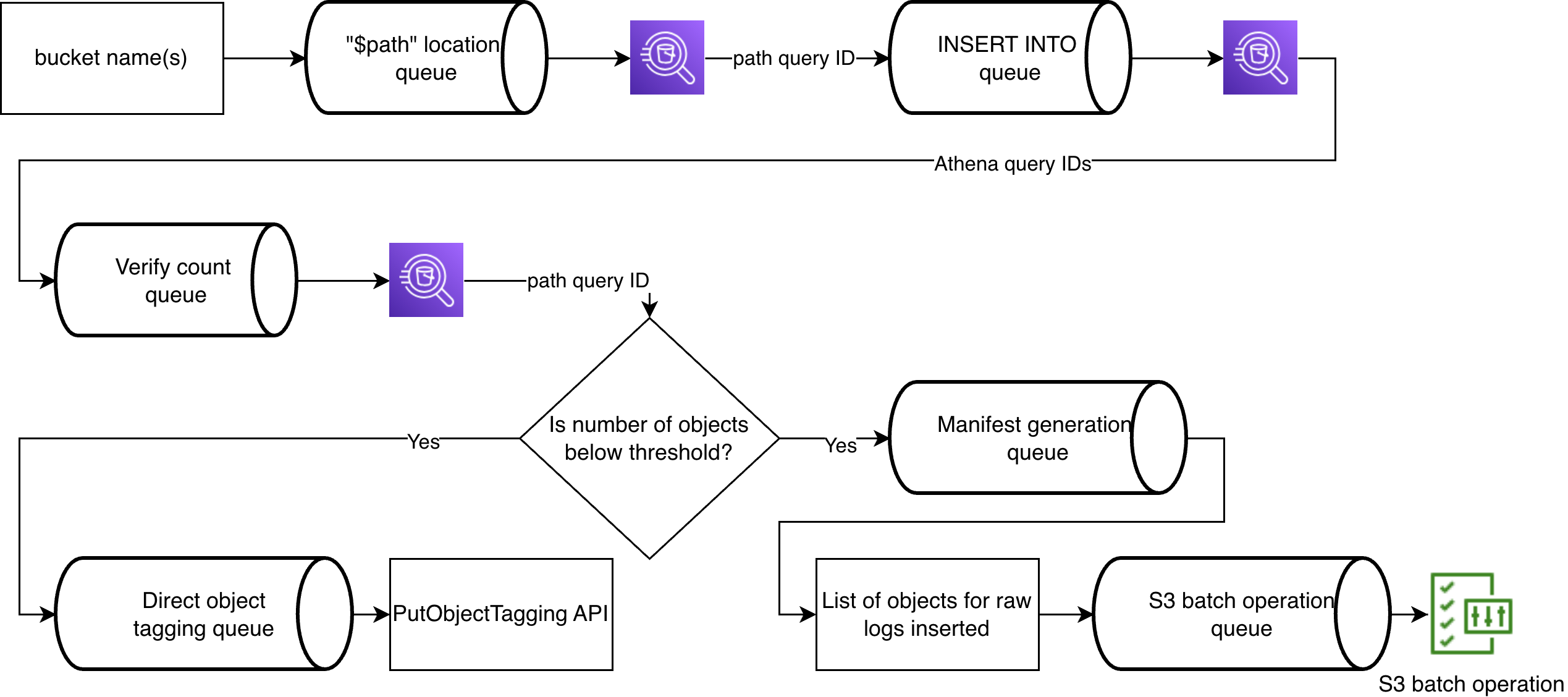

To take advantage of the isolated nature of insertions per bucket, we modeled a queue processing flow using asynchronous functions.

Location query

First, the location query gets objects holding SAL logs that are later marked for expiration after successful insertion. Locations can be retrieved using the $path variable with some string manipulation for S3 batch operation consumption.

SELECT split_part(substr("$path", 6), '/', 1), substr("$path", 7 + length(split_part(substr("$path", 6), '/', 1)))

FROM ...

GROUP BY "$path"

We get locations first in the queue process because it saves us from expiring uninserted logs.

Idempotent insertions

Then, SAL logs are inserted into parquet-formatted tables. A simple insertion query was modified to use left-join on the same partitions, so if there’s a match, then a row won’t be inserted a second time.

INSERT INTO "catalog_target"."database"."table_region"

SELECT *

FROM "catalog_source"."database"."table_region" source

LEFT JOIN "catalog_target"."database"."table_region" target

ON target.requestid = source.requestid

AND bucket_name = 'foo-bucket'

AND timestamp = '2024/01/01'

WHERE bucket_name = 'foo-bucket'

AND timestamp = '2024/01/01'

AND target.requestid IS NULL

Now, we could rerun insertions without having to worry about inserting the same data again. Having the requestid column comes in handy. For tables without a unique column, we’ve used checksum on row values. Duplicating filters for bucket_name and timestamp is prudent because queries start taking longer to run after each insertion. For how we map bucket to Glue catalog, see Mapping bucket to Glue Data Catalog.

Thanks to idempotent Athena queries, our system is retry-safe, and any failure can be fixed by re-running the job over a day’s worth of data.

S3 batch operations

Lastly, manifests, list of objects to tags, are created for S3 batch operations to expire the SAL objects after counts have been verified on source and destination partitions (for more details, see Appendix: Verification of table counts).

Since deletion is not supported by S3 batch operation, and issuing a delete API request per object does not scale well—even with the batch deletion API—we use object tagging for partitions with high volumes of SAL logs.

S3 job incurs $0.25 flat fee on a per bucket basis that becomes the biggest cost contributor so we directly tag objects for most buckets that generate low order access logs.

One additional challenge is that Athena query results include a header row, which S3 batch operations interpret as a bucket name—causing job failures. To work around this, we recreate manifest files in memory without headers. We also ensure that object keys are properly URL-encoded (equivalent to quote_plus(key, safe="/") in Python) before passing them to S3 batch operations.

Joining S3 inventory with S3 server access logs

Access-based tables gather data weekly that determine “prefix” access by disjunction between S3 inventory and a week’s worth of access logs. This ensures that historic data over a long period of time is queryable, and has a small storage footprint.

The prefix covers only immediate keys under it, segmented by slash (/), and removing trailing slash because we wanted to avoid confusion where a prefix “/foo” would determine whether a key “/foo/” was accessed or not, i.e.

SELECT array_join(slice(split(rtrim(key, '/'), '/'), 1, cardinality(split(rtrim(key, '/'), '/')) - 1), '/') as prefix

Being able to determine the prefix from a key turned out to be critical for join operations. Due to the nature of Athena’s distributed node computations, we found out that join-on-equality can distribute work more efficiently across nodes, whereas join-on-like resorts to a cross-join that broadcasts data across all nodes. For example, in a query over ~70,000 rows, simply switching from a LIKE operator to an equality (=) operator reduced execution time from over 5 minutes to just 2 seconds—a dramatic improvement.

Once we have gathered historical data, prefixes from access-based tables are joined back with S3 inventory to get back full S3 object names that are required for S3 batch operation.

Future Work

The project was designed to help close the gap for S3 buckets that do not currently have a lifecycle expiration policy applied to all objects. We are now using access-based retention to delete unused objects. But there are some valid exemptions, such as backup buckets that store incremental changes (CDC) to a table that may appear to contain objects that haven’t been accessed, when in fact it indicates that the data has not changed for the table.

As a potential future enhancement, we’d like to make S3 server access logs easily available for engineers by forwarding them to our data observability platform, Splunk. This would require reducing data volume to meet the target daily ingestion limit and applying shorter retention periods, which would still be sufficient for debugging purposes. Once ingested, logs could be queried more efficiently than through Athena, offering a faster and more cost-effective troubleshooting experience.

Acknowledgements

The idea to convert plaintext logs to parquet-formatted S3 objects through Athena came from Nick Del Nano. The overall effort started as part of unhack work with Thomas Robinson, Quentin Long, and Vincent Thibault that showed storage costs can be reduced to manageable levels.

Huge thanks to Vincent Thibault for setting up the initial infrastructure by enabling logging across all buckets, taking care of dynamic partitioning and coming up with an asynchronous approach to issuing queries. Additionally, Daniel Popescu helped with troubleshooting and providing ideas on reducing operational load for the future on-call person. Quentin Long was the guiding force behind many design decisions and scoping the problem space. And last but not least, Brian Minard kept us on track to meet milestone targets and deliver value to the business needed for the project completion.

Appendix

Idiosyncrasy in key encoding

Initially, we were under the impression that the key is always double url-encoded based on data encountered. So, using url_decode(url_decode(key)) worked until we saw that for some operations, such as BATCH.DELETE.OBJECT and S3.EXPIRE.OBJECT, the key is url-encoded once. Therefore, decoding twice will fail on keys that contain percent (%) symbols as a character. Upon further observation, we have come to a conclusion that lifecycle operations are url-encoded once likely because they come from an internal service. You may think that falling back to single url-decoding is sufficient, but consider the case when a key in access logs is foo-%2525Y - decoding twice succeeds even though its actual object name may not be it, i.e. foo-%Y versus foo-%25Y.

Mapping bucket to Glue Data Catalog

We leveraged Glue Data Catalog to read and write tables across different AWS accounts. This of course requires cross-account access for Glue catalog along with database and tables, meaning both accounts need to allow access to Glue resources, as well as S3 permissions to access underlying S3 objects that store the access logs. Querying data from other accounts involves registering an AWS Glue Data Catalog to be used as from-item in the from-clause.

FROM "catalog"."database"."table_region"

We needed mapping from bucket name to account ID and then to catalog name. Fortunately, getting account ID from bucket name was no extra work because we had data available from previous projects. A mapping between account ID and Data Catalog name is generated via ListDataCatalogs API call.

The names for table and database names could have been made constant across accounts and regions, but we opted to embed the information in the names to be explicit; that occasionally backfires, when a query produces 0 results and you realize that the bucket exists in a different account or region!

Verification of table counts

Athena API call for GetQueryRuntimeStatistics can help to avoid querying for table count since it provides Rows statistics with the number of rows scanned; it’s only accurate for blank insertions because using JOIN will include the row count of all joined tables. For initial insertions, we compare rows scanned from the API - thereby skipping expensive query on SAL objects - against count query on compacted tables, which is fast due to parquet format. The API statistics are served asynchronously, but sometimes the Rows key may not be populated at all. In such cases, we fall back to count queries.

For re-insertions, we use distinct count queries because duplicate logs won’t get inserted into compacted tables which would make counts mismatch for simple count queries. For very rare occasions, it’s possible that a log arrives between insertion and count queries, then insertion query needs to run again.

Join Our Team at Yelp

We're tackling exciting challenges at Yelp. Interested in joining us? Apply now!

View Job